An exceptionally loud collision between two black holes has been detected by the LIGO gravitational wave observatory, enabling physicists to test a theorem postulated by Stephen Hawking in 1971

By Matthew Sparkes

10 September 2025

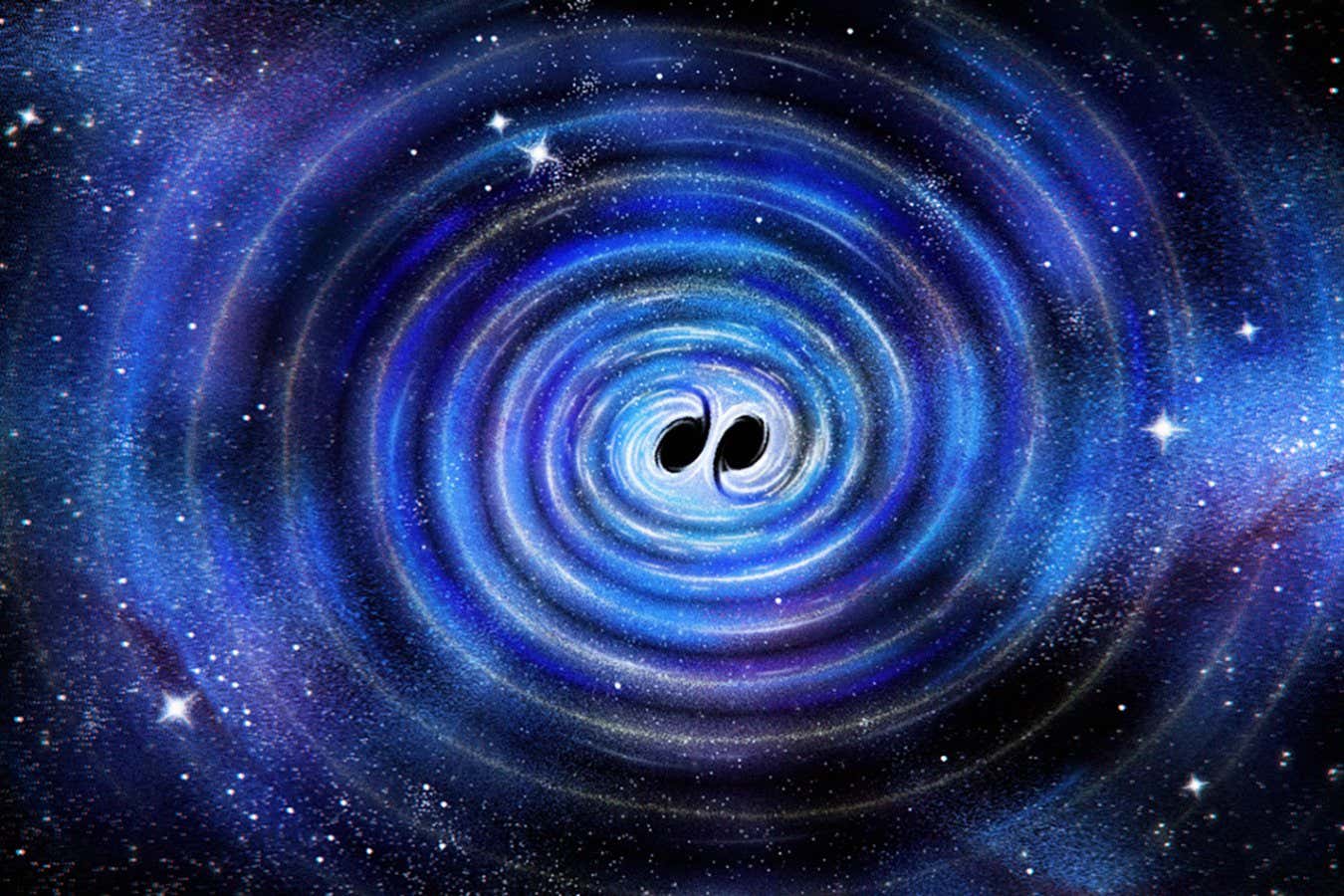

Illustration of two black holes merging and sending gravitational waves across the cosmos

Maggie Chiang for Simons Foundation

Stephen Hawking’s 50-year-old theorem on how black holes merge together has been successfully tested thanks to huge advances in gravitational wave astronomy, which helped astronomers catch the waves caused by an unusually powerful collision as they passed Earth at the speed of light.

Hawking proposed his black hole area theorem in 1971, which states that when two black holes merge, the resulting black hole’s event horizon – the boundary beyond which not even light can escape the clutches of a black hole – cannot have an area smaller than the sum of the two original black holes. The theorem echoes the second law of thermodynamics, which states that the entropy, or disorder within an object, never decreases.

Read more

We are about to hear echoes in the fabric of space for the first time

Advertisement

Black hole mergers warp the fabric of the universe, producing tiny fluctuations in space-time known as gravitational waves, which cross the universe at the speed of light. Five gravitational wave observatories on Earth hunt for waves 10,000 times smaller than the nucleus of an atom. They include the two US-based detectors of the Laser Interferometer Gravitational-Wave Observatory (LIGO) plus the Virgo detector in Italy, KAGRA in Japan and GEO600 in Germany, operated by an international collaboration known as LIGO-Virgo-KAGRA (LVK).

The recent collision, named GW250114, was almost identical to the one that created the first gravitational waves ever observed in 2015. Both involved black holes with masses between 30 and 40 times the mass of our sun and took place about 1.3 billion light years away.

This time, the upgraded LIGO detectors had three times the sensitivity they had in 2015, so they were able to capture waves emanating from the collision in unprecedented detail. This allowed researchers to verify Hawking’s theorem by calculating that the area of the event horizon was indeed larger after the merger.